PIP assessments and me: stuck in the middle with ATOS.

Posted: September 12, 2015 Filed under: benefits, disability, fibromyalgia, PIP | Tags: atos, benefits, chronic illness, chronic pain, fibromyalgia, pip 2 Comments**DISCLAIMER: All the opinions and experiences in this post relate to me. Everyone’s experiences of disability and illness are different and no two people will have the same views, opinions and feeling about the topic.**

Next month, I won’t have worked for two years. It really doesn’t seem that long but it also really does seem that long. I wouldn’t be lying if I said that I don’t know what happened to 2014 and 2015 – a year spent working out what my illness does and how I could live with it, and another year trying to get myself back to as “normal” as I could be while still making accommodations for my condition. Time moves fast when you’re doing very little, it seems.

I’ve had two ATOS assessments in that time, both for PIP. The first one was kind of a blur – I’d been ill for a few months, I didn’t really know what was going on, what medications I should be on, how I was going to pace myself, all the things that you eventually pick up and learn the longer you live with being ill. My second assessment was last week and it was a different experience. Not because it was conducted at home rather than at their offices, or because the questions were different (they weren’t) but because I’ve lived in this body with this condition for nearly two years and I know it a lot better now.

I’ve gone through different stages of dealing with being ill. For a while I was just “ill”. One day I could do something, then over the course of a weekend I just got ill. I can remember the weekend clearly as the Monday was the final time I went into work. Then you start looking for reasons and ways to help. Diagnoses, medications, pacing, reducing the amount you achieve in a day. Resting a lot. Sleeping a lot. Getting into the groove of “being ill”.

And then once you’ve got the rhythm of your illness – you’ve worked out that your big flares usually come a week after the event that triggers them, that if you spend the morning in town you’d better not plan any activities for the afternoon, that if you’re going to need to be clean and showered for some reason you’d best plan that into your previous day (also your definition of “clean” gets reeealllly loose…) – you start to live with it rather than fight against it. This doesn’t mean everything is roses and happiness, far from it. You get days of pain and days of exhaustion, you can’t drive as far as you used to or walk as far or be able to use your brain and think after 3pm. But you have what I called my “new normal” – and you forget that this isn’t other people’s normal.

I’ve found myself stuck in a really bizarre place. I’ve just finished a postgraduate degree and I’ve worked for ten years in a profession (granted the profession has been ripped to pieces by the Tories but I digress…) and so my desire is to work, because I love my profession and I want to be able to practice it. But then, you’re put in a position with your ATOS assessor where you have to describe in minute detail how you can’t always cook your own meals, how sometimes you don’t have the energy to wash your own hair, how someone else has to come in and do your vacuuming for you. I’ve found it very difficult to take both the realities of being a professional, and of someone who is ill and needs assistance and help with everyday tasks, and apply them to the same person – me. How can I be both those people at once?

And I know where this confusion comes from. Having an ATOS assessment makes you constantly second-guess yourself. Can I walk further than I said I could? If I can open a can now does that mean I can actually cook? Am I better than I was, am I more able than I think I am, am I being lazy? The constant second-guessing and the need to prove that you’re ill or disabled makes you stand face to face with the worst bits of your illnesses. I can’t leave the house for days, I can’t wash my hair more than once a week, I can’t cook my own dinners. It’s almost impossible, to me at least, to take that view of myself and pair it with “I’m a professional with a postgraduate degree and the desire to work”. The DWP make disabled and ill people justify the worst of themselves and then they expect them to “pull up their bootstraps” and make the best of the situation. After you’ve been repeatedly shot down by churning out all the reasons your mind and body is unable to work properly, under the fear that you won’t be believed, it’s a difficult task to turn that around and be motivated and positive.

But hey, maybe that was their plan all the time. Motivated and positive ill and disabled people get ideas and opinions and the means to express them, and we can’t be doing with that.

ATOS and my new normal.

Posted: August 21, 2015 Filed under: benefits, disability, fibromyalgia, PIP | Tags: atos, benefits, chronic illness, chronic pain, disability, fibromyalgia, pip 1 Comment So, once again, ATOS and I are going to spend an hour hanging out together. Although this time they’ve invited themselves round to mine. They’d better not be expecting a finger buffet.

So, once again, ATOS and I are going to spend an hour hanging out together. Although this time they’ve invited themselves round to mine. They’d better not be expecting a finger buffet.

It’s strange, because obviously I have a lot of things to say about this. I have to go for another assessment after having been on PIP for just a year which really wasn’t expected, but they were a hell of a lot faster this time than last I’ll give them that. I’m going into this one having already had one assessment and so I know a bit more about how the process works, but I feel like I can’t talk about much of that at the moment. Because the internet has ears. And the paranoia of ill and disabled people is high. And I’m worried that my concerns about my assessment will be taken the wrong way. So instead, I thought I’d talk about something else.

I got ill almost two years ago now. It seems like yesterday and a lifetime ago at the same time. When I look back at how I was before I got ill, the work I did, the activities I did, how busy I was, it definitely seems like another life. And the problem with that is, the way I am now has become normalised in my mind. And so I forget that I still do things differently in order to accommodate my condition because I’m now not aware that I do them.

I don’t go into town because I know it’ll make me tired and I have things to do at home. I have to plan my showers days in advance sometimes, to make sure I’m actually, y’know, clean but to make sure I have time to rest afterwards. I get tired in the afternoons. I get pain and fatigue when it rains. I take strong painkillers, I don’t clean my own house, and just today I vetoed a trip to the supermarket at the end of the road because I felt in too much pain (even though I would’ve driven there rather than walked).

But that’s now my “normal”. I do all these things without thinking about it because it’s habit. Which worries me that I might miss them when I’m talking to the ATOS person.

Last time I said it felt like an exam. So I guess it’s time to start revision.

Frustration.

Posted: April 25, 2014 Filed under: disability, fibromyalgia | Tags: chronic illness, chronic pain, disability, fibromyalgia, spoonie Leave a commentMy PIP application and OT referral were submitted in February. I don’t expect to hear anything soon.

Various doctors (and a practice nurse) at my GP surgery have told me to increase, then decrease, then increase my medication. I am in constant pain but won’t be given stronger painkillers. I am in constant pain but am not allowed a referral to the pain clinic until I’ve been on my current medication (amatriplyline, 50mg) for a month, and then I have to try another medication (gabapentin), and then I might be allowed a referral. I am currently not under the care of any specialists.

I’ve realised I cannot do the work I so desperately want to do because I will not be able to manage it. I cannot get out of the house because I can’t drive very frequently any more, and leaving the house exhausts me. I am not eligible for social care.

So I can’t work, I’m in constant pain and I’m refused better pain medication or access to specialist care.

Exactly what the hell am I supposed to do now?

None of the “cool” doctors want to treat fibromyalgia.

Posted: March 21, 2014 Filed under: activism, disability, fibromyalgia | Tags: chronic illness, chronic pain, fibromyalgia, spoonie 7 CommentsFibromyalgia just ain’t cool. And there’s statistical research to back it up.

Respondents [senior doctors, GPs and final year med students] were asked to rank 38 diseases as well as 23 specialties on a scale of one to nine. …Myocardial infarction, leukaemia, spleen rupture, brain tumour, and testicular cancer were given the highest scores by all three groups. Prestige scores for fibromyalgia, anxiety neurosis, hepatic cirrhosis, depressive neurosis, schizophrenia, and anorexia were at the other end of the range.

It doesn’t show it very accurately in that quote, but the most “prestigious” disease to treat came up as MI, and the least was fibromyalgia. Colour me unsurprised. Two of the “popular” diseases occur mainly in men (especially as one of them involves have a specific set of genitals). Two of the least “popular” diseases occur mainly in women. All of the “popular” ones are dramatic conditions, which either involve slicing someone open and tinkering with a specific body part or a thin line between life and death. The unpopular ones are mostly mental health, except for fibromyalgia (which a lot of doctors would say is in your head anyway) and heptic cirrhosis (found in alcoholics, so I imagine there’s a large “you brought this on yourself” element.)

To some extent, I see where they’re coming from. In the life of a doctor, the ER moments where a patient has blood spurting from many orifices and they’re on the verge of death are no doubt seen as very exciting. Similarly, getting to do brain surgery would earn you a lot of kudos. But I think there are some other themes that can be drawn out of this:

- You have to be able to see the condition, either physically or through a scan of some kind.

- There has to be a medicine or procedure available to fix said condition

- Mental health conditions are boring to treat

- Especially women’s mental health

- Especially women’s health issues where there isn’t a clear way to diagnose

Fibromyalgia doesn’t have a test to diagnose it, you can’t give drugs to cure it. It’s found mostly in women and you can’t physically see it. It doesn’t cause life-or-death blood spurting moments (I hope…) and so it’s a boring disease. So doctors aren’t willing to put in the effort to research it. It’s much easier to say “here’s a pill, it might help, go swimming and cut out the gluten” and send them on their merry way. While possibly thinking “she’s just hysterical, it’s probably all in her head.”

It is obvious that no-one is going to make a fuss about this condition, because so very few medical professionals actually care about researching what it is that makes us so chronically ill. So, as I’ve said before, that is why it is up to us, the chronically ill, to become the professionals. From our beds and sofas, in our pyjamas with our heat pads and blankets. And possibly stoned out of our gourds on heavy pain medication.

“I have this belief that if I can read a lot of science and do a lot of self-experimentation then I can turn this thing around.”

– Jen Brea, Canary In A Coalmine trailer

From now until the end of April, I’m going to spend as much time as I can manage researching. I’m going to read about what the latest research on fibromyalgia is telling us. I’m going to teach myself the arguments from the pro-psychosomatic camp and the pro-medical camp. I’m going to learn about what people think fibromylagia is, what treatments have been tested and what’s worked. Because no-one else is going to be interested in becoming an expert on my condition. So I’m going to become one myself.

So, this blog is going to come pretty fibromyalgia/chronic illness focussed for a while. There probably won’t be many youth work posts for a bit, but they will come back eventually. I just feel like I need to know what’s going on with my own body.

“Medically Unexplained Symptoms”

Posted: March 3, 2014 Filed under: disability, fibromyalgia, government | Tags: chronic fatigue syndrome, chronic illness, chronic pain, disability, fibromyalgia, Myalgic Encephalomyelitis 9 CommentsOne of the biggest challenges faced by people who have chronic illnesses is that of being believed. Of being listened to by professionals, and finding people who understand that conditions like fibromyalgia, M.E. and so on are real, physical illnesses. After my encounter with the rheumatologist last week, I went back to a post that had been flagged up in the FibroME For Action Facebook community (link in the side bar) about the Barnet Clinical Commissioning Group’s pilot study in managing people with “Medically Unexplained Symptoms” (MUS). (more info here on the dx revision watch website)

This all sounds like a bunch of NHS jargon-speak, which it is, but essentially they were putting forward the idea that people with MUS (which they class as fibromyalgia, M.E, chronic pain, post-viral fatigue, CFS and “somatic anxiety/depression”) shouldn’t be referred on to secondary care (rheumatologists etc.) but should stay under the management of GPs . The purpose of this?

- “Reduced GP secondary [rheumatology, physio, OT etc] and tertiary [inpatient programmes] referrals.”

- “Reduced unnecessary hospital investigations and prescribing of medicines”

- “Reduced GP appointments and out of hours appointments to A&E or GP”

So, a pilot that’s designed to reduce access to specialists and prescribed medicines for people with conditions like fibromyalgia, M.E. and other chronic pain disorders . Well this can’t possibly go wrong.

This is clearly a cost-reducing exercise. But the NHS can’t just say “sorry, you’re just too expensive to treat” and needs to give some kind of reasoning behind their actions. Let’s start by having a look at how they describe those of us with “MUS”:

“Other terms used to describe this patient group include:…Bodiliy Distress Syndrome (BDS)”

Remember where we’ve seen that term used before? Our friend Dr. Fink, who considers these conditions to be mental disorders. So that’s concerning, for a start.

There’s another document here that goes into a bit more depth about exactly what people with MUS are like (other than “generally annoyed and in pain”, obviously). I want to highlight some choice quotes:

- “MUS cannot be easily ascribed to recognised diseases. They might be caused by physiological disturbance, emotional problems or pathalogical conditions which have not yet been diagnosed.”

- “More common in women”

- “Past health and psycosocial experiences may encourage some patients to minimise certain symptoms and over emphasise others to shift the doctor’s attention in a particular direction.”

- “Most people with MUS who see their GP will improve without any specific treatment”

This paints chronic illness patients as manipulative and hysterical. GPs are being told that anyone with an “MUS” doesn’t need to be referred to a specialist, that our symptoms are “emotional problems” and that we’re likely to try and manipulate our doctors to get what we want. Anyone who has been to a cynical doctor knows that sometimes, focusing on one particular symptom is the only way to get them to listen to you so you can get the treatment you need.

Here’s another quote from the same document:

“For MUS, good practice consensus recognises that not investigating may be best for the patient.”

The document recommends that to investigate – to give “credibility” to our pain and fatigue – is not good practice. This attitude belittles us, patronizes us and says “doctor knows best”.

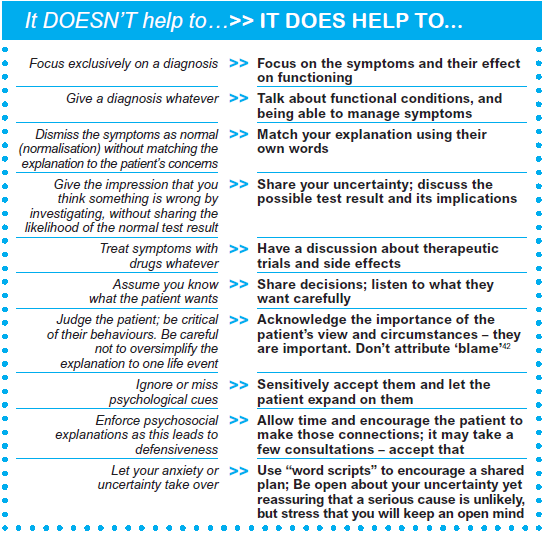

Focus on managing symptoms rather than getting a diagnosis, don’t treat with drugs, saying that “a serious cause is unlikely”. This puts conditions like fibromyalgia, M.E., et al. under the “not so bad” group. And then we’re back to “just get some more exercise” as a cure.

This is dangerous. I believe this is an unsafe way to practice medicine. To tell medical professionals that when people come to their surgeries with medically unexplained symptoms, you don’t investigate to see what the problem is. This is why we are facing a massive lack of research into conditions like fibromyalgia and M.E. We are fighting a long battle to get the medical profession as a whole to treat these as conditions and diseases, rather than just a pile of “unexplained” symptoms. They’re being told it’s not worth their time, that it’s a waste of money and resources. That we are not worth the trouble. That, quite frankly, is appalling. Once again, it comes down to the tired, sick, exhausted and chronically ill to do their own research and fight the battle.

If you don’t look for a diagnosis but just manage the symptoms, people with chronic illnesses will go undiagnosed. They will not get the correct treatment. This is how we end up with people getting psychological treatment for a physical illness. Figures for the prevalence of illness will be inaccurate, and it will be very difficult to make the case for more research into these conditions.

I believe we need to be doing more research into these chronic conditions so we can find a cure for them. The attitude at the moment that “managing” the symptoms is enough. Please do read the documents I’ve linked to, I’m really interested in hearing other people’s views on what they say. And then let’s work out how we can change this.